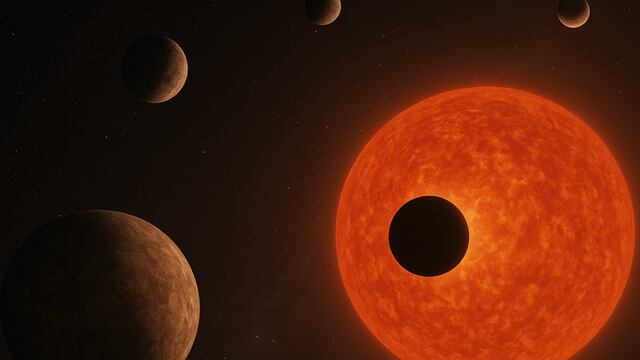

For decades, scientists have searched the skies for worlds beyond our solar system that resemble Earth — planets with the right size, right temperatures, and a stable atmosphere where liquid water could exist. Now, recent research using some of NASA’s most powerful telescopes suggests we may be closer than ever to identifying such a world. Several lines of evidence from NASA missions and international science teams point toward the exoplanet TRAPPIST‑1 e as one of the most intriguing candidates yet — a planet located about 40 light‑years away that may harbor an atmosphere and conditions suitable for liquid water.

Why does this matter? Water and a stable atmosphere are considered essential ingredients for life as we know it. Earth itself hosts life because its atmosphere traps warmth and its surface water supports a biosphere filled with chemistry far more complex than that on dry, barren worlds. If TRAPPIST‑1 e — or a similar exoplanet — has these features too, it raises one of the biggest questions in science: Is Earth unique? Or are planets with life‑friendly environments common across the galaxy?

How We Find and Study Exoplanets

Before diving into TRAPPIST‑1 e, it helps to understand how astronomers find and analyze these distant worlds — a remarkable achievement of modern astronomy.

Most known exoplanets are detected using the transit method, where telescopes watch a star’s light dip slightly as a planet passes in front of it. By measuring these tiny dips, scientists can calculate a planet’s size, orbit, and sometimes even features of its atmosphere.

The real breakthrough in recent years has come from spectroscopy — studying the light that filters through a planet’s atmosphere as it transits its star. Different molecules absorb light in unique ways, leaving fingerprints in the star’s spectrum that reveal what gases might be present around the planet. This technique has allowed astronomers to detect water vapor, methane, and other gases in exoplanet atmospheres, even though these worlds are light‑years away.

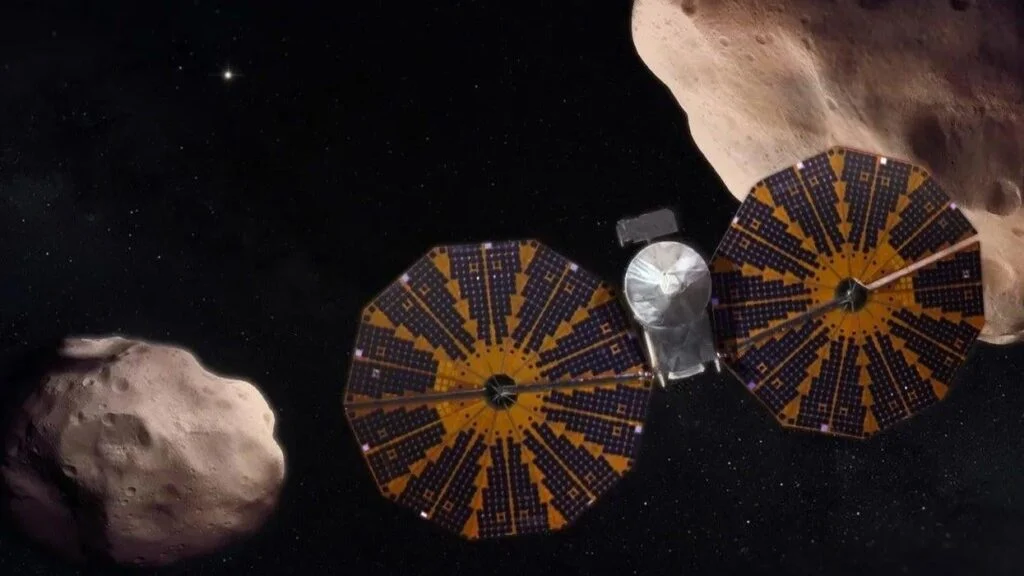

Two telescopes have been most important for this research:

🇺🇸 NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope — Though launched in 1990, Hubble still contributes to exoplanet science by providing ultraviolet and visible light spectra. It helped first hint at water content on planets orbiting distant stars.

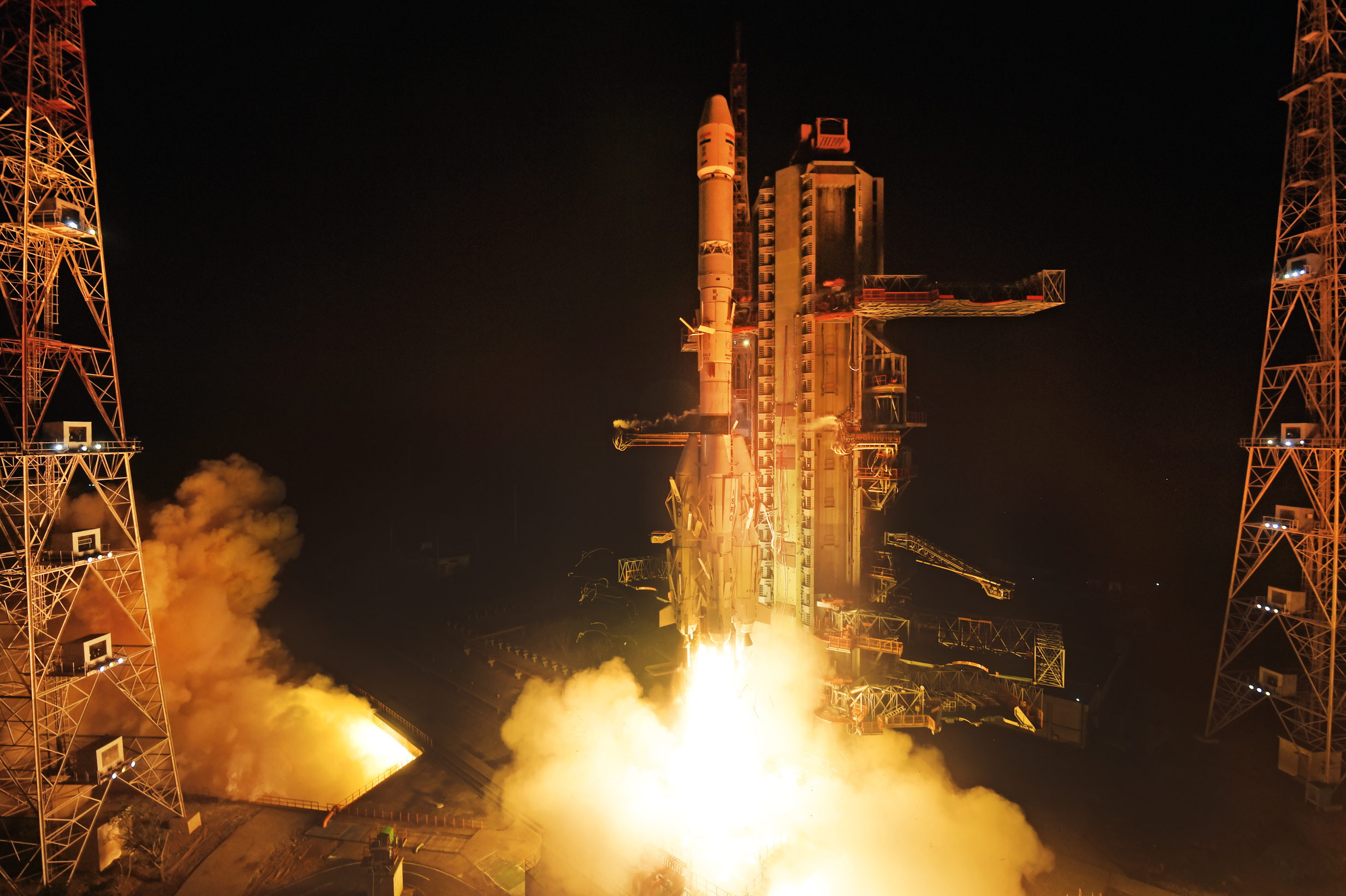

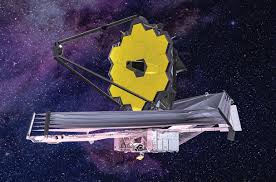

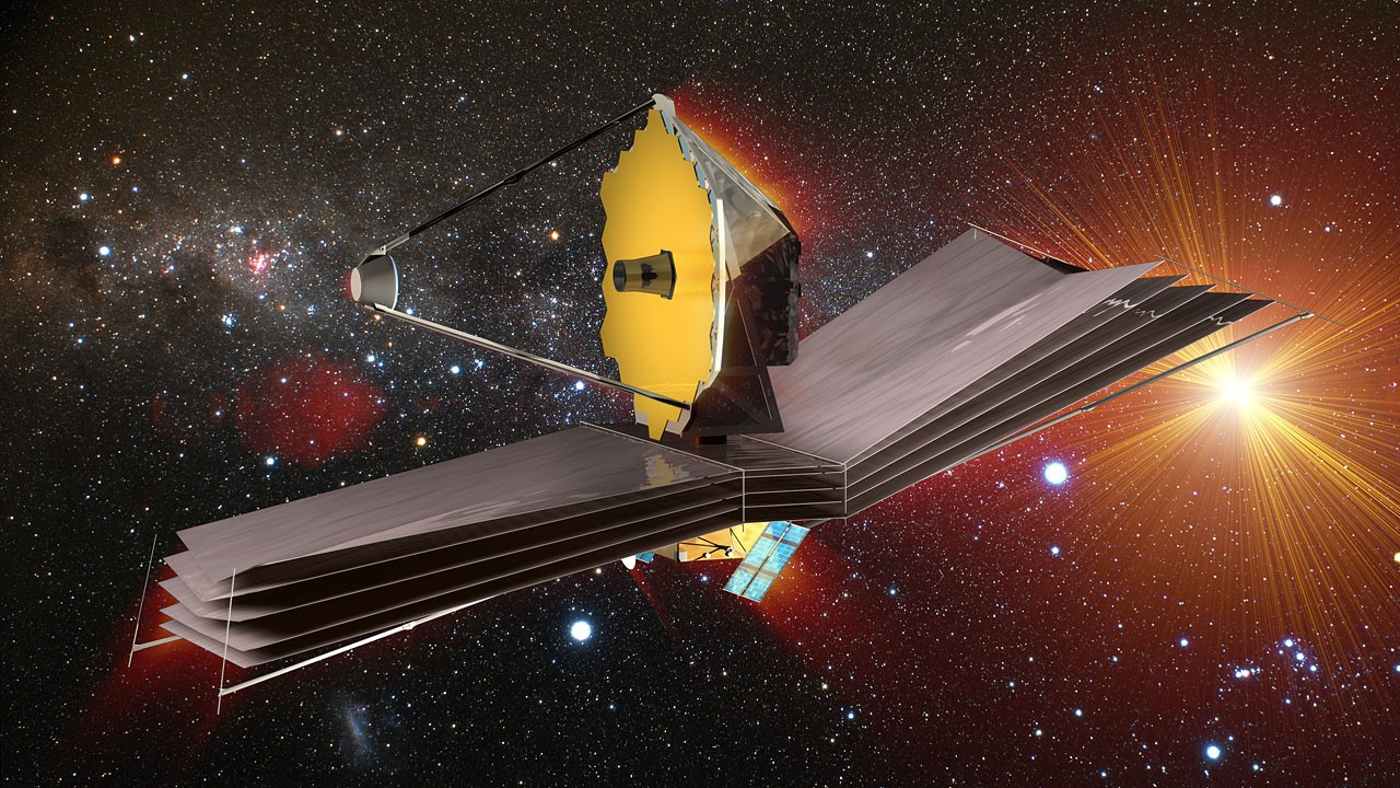

🇺🇸 NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — Launched in 2021, Webb’s advanced infrared instruments are uniquely capable of teasing out faint atmospheric signatures from rocky, Earth‑like planets. It is in many ways the most powerful tool ever used to search for potentially habitable worlds.

Meet TRAPPIST‑1 and Its Family of Planets

TRAPPIST‑1 is a small, cool star known as an ultracool dwarf, roughly the size of Jupiter and much cooler and dimmer than our Sun. In 2016, an international team of astronomers discovered seven Earth‑sized planets orbiting this star — more rocky worlds than any other system so close to us.

These planets orbit very close to their star, completing circuits in just days to weeks. But because the star is so dim, some of them sit in the habitable zone — the range of distances where temperatures might allow liquid water to persist on the surface. Out of the seven, three are thought to be in this so‑called “Goldilocks zone,” and TRAPPIST‑1 e is one of them.

What Makes TRAPPIST‑1 e Special?

Earth‑Sized and in the Right Place

TRAPPIST‑1 e is roughly the same size as Earth, making it easier to compare its potential conditions to our home planet than larger gas giants or “super‑Earths.” Its orbit lies within a region where, given the right atmosphere, temperatures could be just right for liquid water.

Hints of an Atmosphere

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have collected data on TRAPPIST‑1 e’s transit signals. While the results are still being analyzed, early findings suggest that the planet may indeed have an atmosphere — a crucial prerequisite for holding heat and possibly water.

Unlike Earth, a planet does not necessarily need exactly the same atmosphere to be habitable, but it must have some form of gaseous envelope thick enough to maintain surface pressure and temperature. Detecting signs of even a modest atmosphere around a rocky world this distant is a major scientific accomplishment.

Potential for Liquid Water

An atmosphere alone isn’t enough; water must exist in liquid form on the planet’s surface or within shallow oceans. So far, researchers are careful to say that water is not yet confirmed on TRAPPIST‑1 e. But the possible presence of an atmosphere — along with its position in the habitable zone — makes water seem more plausible than many other exoplanets studied to date.

Water vapor signatures are easier to detect in gas giants, but finding similar signatures on a rocky Earth‑like planet would be groundbreaking. This is exactly what scientists are trying to achieve with JWST’s infrared spectroscopy.

What NASA and Scientists Are Actually Saying

Let’s be clear: no one has yet declared TRAPPIST‑1 e a “second Earth.” That title carries immense implications — biologically, socially, and scientifically — and scientists are cautious. But here’s what the data does indicate so far:

TRAPPIST‑1 e is one of the best Earth‑like candidates we’ve found.

Its size, orbit, and position in the habitable zone make it a prime target for detailed atmospheric study.

Early observations show possible atmospheric signals.

While not yet definitive, hints from the James Webb telescope suggest there could be an atmosphere present.

If there is an atmosphere, liquid water becomes far more plausible.

With atmospheric pressure and the right temperature balance, water could persist as a global ocean, lakes, or ice — depending on conditions.

No confirmed detection of water yet.

Atmospheric water signatures are complex to interpret, and scientists need more data before making any definitive claims.

No signs of life (yet).

Detecting water and an atmosphere is one thing — detecting biological activity is much harder. Future observations targeting specific biosignatures (like oxygen, ozone, methane combinations, or unusual atmospheric chemistry) would be needed before there’s any talk of life.

Why This Discovery Matters So Deeply

The search for Earth‑like planets is more than a scientific curiosity — it goes to the heart of one of humanity’s biggest questions: Are we alone?

If worlds similar to Earth are common in our galaxy, and they have liquid water and stable atmospheres, the chances that life could evolve elsewhere increase dramatically. Findings like those around TRAPPIST‑1 e don’t prove alien life exists, but they open the door to a future where such a discovery might be possible.

For decades, astronomers have looked at our solar system’s habitable zone — where Earth sits between Mars and Venus — and wondered if similar zones exist around other stars. With data from telescopes like Kepler, TESS, Hubble, and now Webb, we now know:

-

There are billions of planets around other stars in our galaxy.

-

A significant fraction could be rocky and in habitable zones.

-

Some may have atmospheres capable of supporting liquid water.

This doesn’t mean Earth is common — only that Earth‑like conditions might not be as rare as once thought.

What’s Next in the Search for Life

Science doesn’t stop with one set of observations. Astronomers are already planning:

More JWST observations

Webb will continue studying TRAPPIST‑1 e and other promising candidates to refine atmospheric models and detect specific gases.

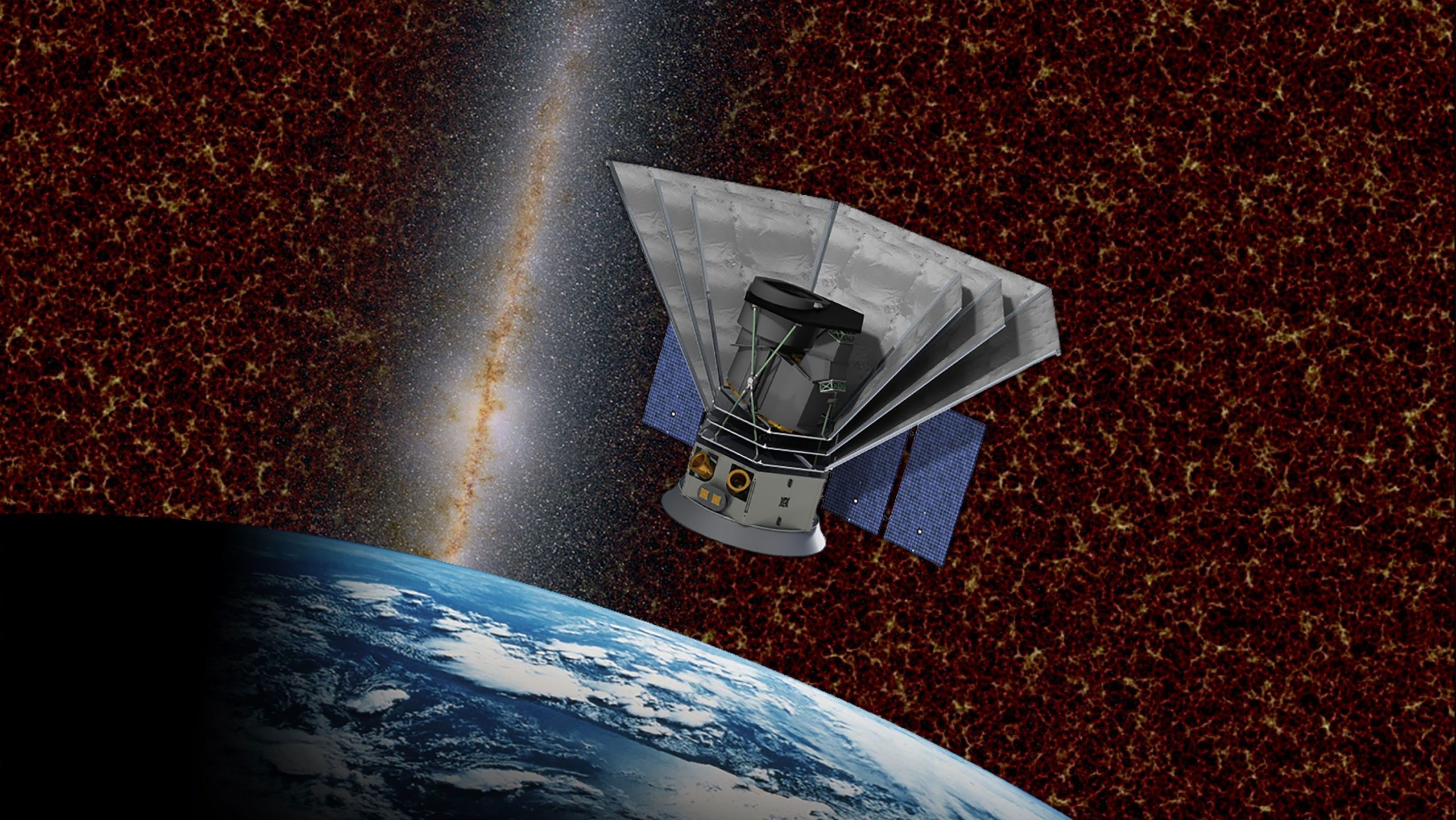

Next‑generation telescopes

Future missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and proposed direct imaging space observatories will even aim to photograph exoplanets directly and search for unmistakable signs of life.

Search for biosignatures

Beyond water, scientists want to find chemical combinations — like oxygen with methane — that on Earth are strongly linked to biological activity. Discovering such biosignatures on another world would be revolutionary.

Conclusion — A Step Toward Answers, Not Exact Replacements

So, is TRAPPIST‑1 e a new Earth? Not yet. But it may be the closest thing we’ve found so far — a planet with Earth‑like size, location, and possible atmospheric conditions that make liquid water plausible. If confirmed with further data, these features would place TRAPPIST‑1 e among the most promising targets in the search for another habitable world in the galaxy.

Every new piece of information about exoplanet atmospheres brings us closer to answering the greatest cosmic question of all: Are we alone in the universe? While we don’t have a definitive “second Earth” yet, each discovery brings that exciting possibility into sharper focus.

Read Also: Keep your face towards the sunshine and shadows will fall behind you

Watch Also: https://www.youtube.com/@TravelsofTheWorl

Leave a Reply