The word “planet” may seem straightforward, yet it has been a source of debate for decades. From Mercury to Neptune, planets are familiar celestial bodies, but their classification has proven far from simple. The controversy reached a peak in 2006, when Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). Since then, scientists have continued to question whether the IAU’s definition is sufficient and whether it accurately reflects the diversity of planetary bodies in our universe. Recently, researchers have proposed an improved definition of a planet, aiming for a more inclusive, scientifically robust, and universal classification.

The Historical Background

The term “planet” originates from the Greek word “planētēs”, meaning “wanderer,” because planets move across the sky relative to fixed stars. Early astronomers observed only those visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Earth itself was later recognized as a planet after the heliocentric model, proposed by Copernicus, displaced the geocentric model.

Over time, new planets were discovered:

-

Uranus in 1781 by William Herschel.

-

Neptune in 1846 by Urbain Le Verrier and Johann Galle.

-

Pluto in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh.

As astronomers discovered more celestial objects, it became clear that a precise definition was necessary to categorize planets consistently.

The IAU Definition

In 2006, the IAU formalized a definition to resolve ambiguities. According to the IAU, a planet must:

-

Orbit the Sun

-

Have sufficient mass to assume a nearly round shape

-

Have cleared its orbital neighborhood

This definition demoted Pluto to a dwarf planet, sparking public debate and raising questions about the adequacy of the criteria. Critics argue that the definition is too restrictive, Sun-centric, and inconsistent with the growing number of exoplanets and dwarf planets.

Problems with the IAU Definition

The IAU definition has several notable shortcomings:

1. Sun-Centric Limitation

The IAU criteria only apply to objects orbiting the Sun. Exoplanets, which orbit other stars, are excluded from this definition, despite clearly fitting other planetary characteristics. With thousands of exoplanets discovered, a planetary definition limited to our Solar System is outdated.

2. Orbital Clearing Ambiguity

The requirement to “clear the orbit” is difficult to quantify. Many planets share space with smaller objects, including asteroids or Trojan companions. Does this mean they fail the planetary test? Such ambiguity highlights the arbitrary nature of this criterion.

3. Exclusion of Rogue Planets

Rogue planets, which do not orbit any star, are excluded under the IAU’s rules, even though they are spherical, massive, and formed like planets. These wandering worlds challenge the traditional understanding of what it means to be a planet.

4. Gray Areas with Dwarf Planets

Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake share many characteristics with planets but do not dominate their orbits. The current definition creates a gray zone between planets and dwarf planets, leaving room for inconsistency.

Scientists Propose an Improved Definition

Recognizing these limitations, planetary scientists have proposed a more inclusive, geophysical definition of a planet. Key aspects include:

1. Intrinsic Characteristics

Instead of relying on orbital dominance, the geophysical definition emphasizes the object’s intrinsic properties:

-

Sufficient mass for self-gravity to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round shape).

-

Mass insufficient for nuclear fusion (distinguishing planets from stars).

This approach includes planets, dwarf planets, and even rogue planets, creating a universal classification applicable throughout the galaxy.

2. Formation-Based Perspective

Some scientists suggest defining planets based on their formation process:

-

Planets form from protoplanetary disks surrounding stars.

-

Objects formed via gravitational collapse, like brown dwarfs, are not considered planets.

This emphasizes the origin of the body, not just its present characteristics.

3. Universality

A modern planetary definition should apply to:

-

Exoplanets orbiting other stars.

-

Rogue planets drifting through space.

-

Dwarf planets like Pluto, Eris, and Ceres.

This universality reflects the diversity of planetary systems and avoids the arbitrary Sun-centric bias of the IAU’s definition.

Advantages of the Improved Definition

-

Inclusivity: All planets, regardless of orbit or location, are recognized based on physical and formation characteristics.

-

Scientific Clarity: Researchers can consistently classify celestial objects without ambiguous orbital criteria.

-

Compatibility with Exoplanet Science: Thousands of exoplanets discovered beyond our Solar System are easily classified.

-

Flexibility for New Discoveries: The definition accommodates unusual or extreme worlds, such as puffy gas giants, icy dwarf planets, and rogue planets.

Examples Illustrating the Need for an Improved Definition

1. Pluto and Dwarf Planets

Pluto’s demotion exemplifies the limitations of orbital dominance as a criterion. Geophysical definitions would retain Pluto as a planet while acknowledging its small size and shared orbital space.

2. Rogue Planets

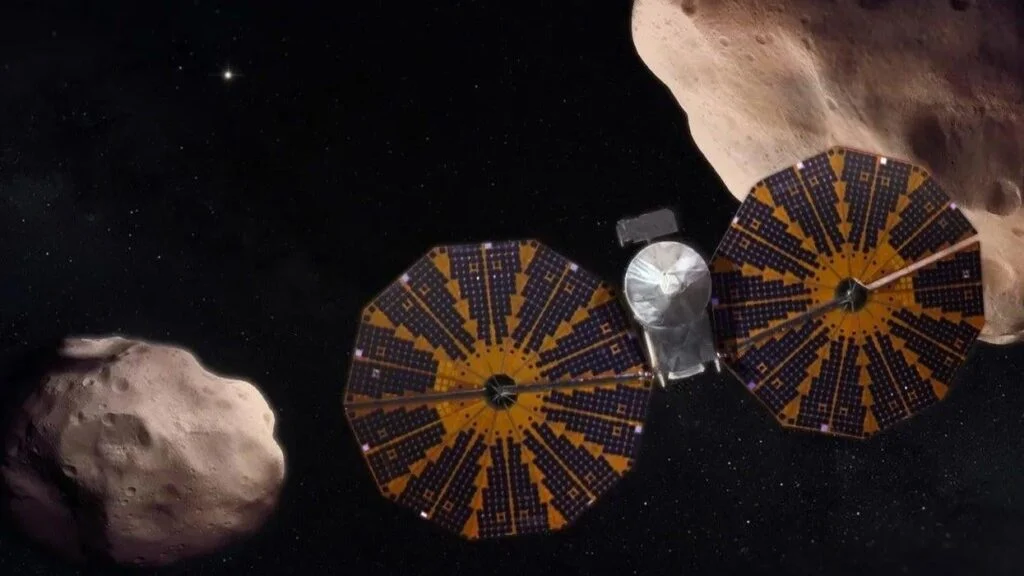

Astronomers have detected free-floating planets that do not orbit a star. Traditional definitions exclude them, yet these planets formed like others and meet geophysical criteria.

3. Puffy Gas Giants

Some exoplanets, known as hot Jupiters, have inflated radii relative to their mass. Current definitions do not account for these unusual characteristics, but improved definitions based on intrinsic properties do.

Implications for Astronomy

Adopting an improved planetary definition impacts science in several ways:

-

Planetary Formation Studies: Understanding diverse planets helps refine models of how planets form and migrate.

-

Exoplanet Research: A universal definition ensures consistency in cataloging and analyzing exoplanets.

-

Education and Outreach: A clear, inclusive definition simplifies teaching planetary science and reduces public confusion.

-

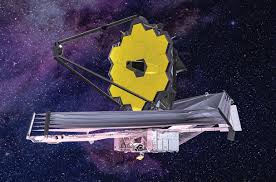

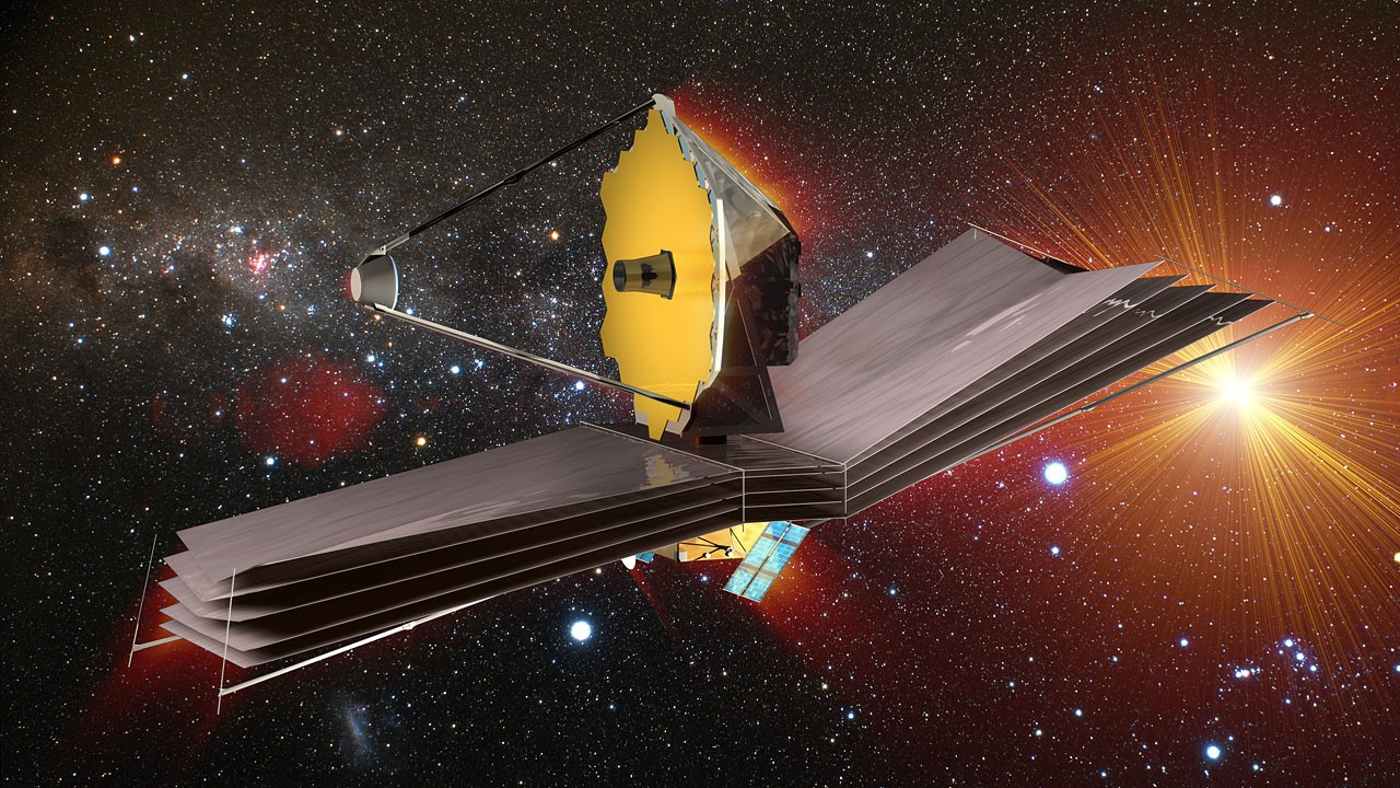

Future Discoveries: As telescopes like James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and upcoming missions explore distant planetary systems, a flexible definition is essential.

Public Perception and Culture

Pluto’s story illustrates how planetary classification affects the public:

-

Education: Textbooks and classrooms had to adjust after Pluto’s demotion.

-

Cultural Impact: Pluto remains iconic in cartoons, movies, and literature.

-

Engagement: Debate over Pluto sparked widespread interest in astronomy, showing how definitions shape public perception.

A modern, inclusive definition can maintain public engagement while providing scientific clarity.

Challenges and Considerations

While the improved geophysical definition has many advantages, challenges remain:

-

Measuring Properties: Determining shape, mass, and formation history requires advanced observation, which may not always be feasible for distant objects.

-

Historical Attachments: People are emotionally attached to traditional planets like Pluto. Changing definitions may face cultural resistance.

-

Consensus Building: The astronomical community must reach consensus to adopt a universally accepted, updated definition.

Despite these challenges, the improved definition aligns with modern science and the realities of a diverse cosmos.

Future Directions

As astronomy advances, planetary definitions are likely to evolve further:

-

Exoplanet Catalogs: Improved definitions facilitate consistent classification of thousands of new exoplanets.

-

Rogue Planet Studies: Understanding free-floating planets will refine planetary physics and formation models.

-

Extreme Planetary Worlds: Puffy gas giants, icy dwarf planets, and unusual exoplanets challenge existing categories, emphasizing the need for flexible definitions.

-

Global Consensus: A geophysical and formation-based approach can unify the scientific community and provide clarity for future discoveries.

Ultimately, the goal is a definition that reflects the diversity of planets, supports scientific research, and is adaptable to new findings.

Conclusion

The question “What exactly is a planet?” has evolved from ancient observation to modern astrophysics. While the IAU’s 2006 definition provided structure, it is limited by Sun-centric criteria, orbital ambiguity, and exclusion of dwarf and rogue planets. Scientists now propose an improved, geophysical and formation-based definition, focusing on intrinsic properties and universal applicability.

This modern definition embraces Pluto, dwarf planets, exoplanets, and rogue planets, reflecting the diversity of planetary systems across the universe. By shifting from rigid orbital criteria to intrinsic characteristics, astronomers aim for a classification system that is scientifically robust, inclusive, and adaptable to future discoveries.

Planets are more than wandering celestial bodies; they are dynamic, varied worlds that challenge our understanding and inspire exploration. A clearer, improved definition ensures that science can keep pace with discovery while capturing the richness of the cosmos for generations to come.

Read Also: Keep your face towards the sunshine and shadows will fall behind you

Watch Also: https://www.youtube.com/@TravelsofTheWorld24

Leave a Reply