For centuries, humans have looked up at the night sky, fascinated by the wandering lights we call planets. From Mercury to Neptune, these celestial objects have long been considered distinct from stars and asteroids. Yet, despite centuries of study, the definition of a planet remains surprisingly controversial. Even today, debates rage over what truly qualifies as a planet and why some objects, like Pluto, no longer fit the category. This controversy reveals fundamental flaws in how we classify celestial bodies, highlighting both scientific and philosophical questions about how we understand our universe.

The Historical Definition of a Planet

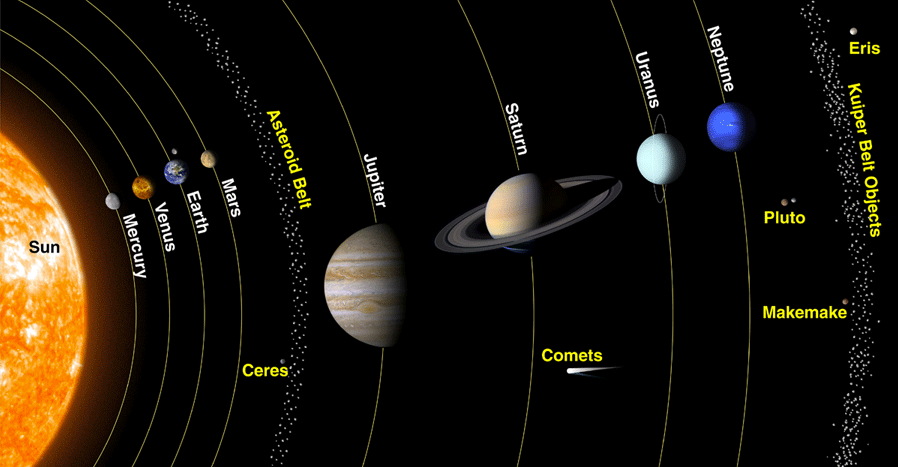

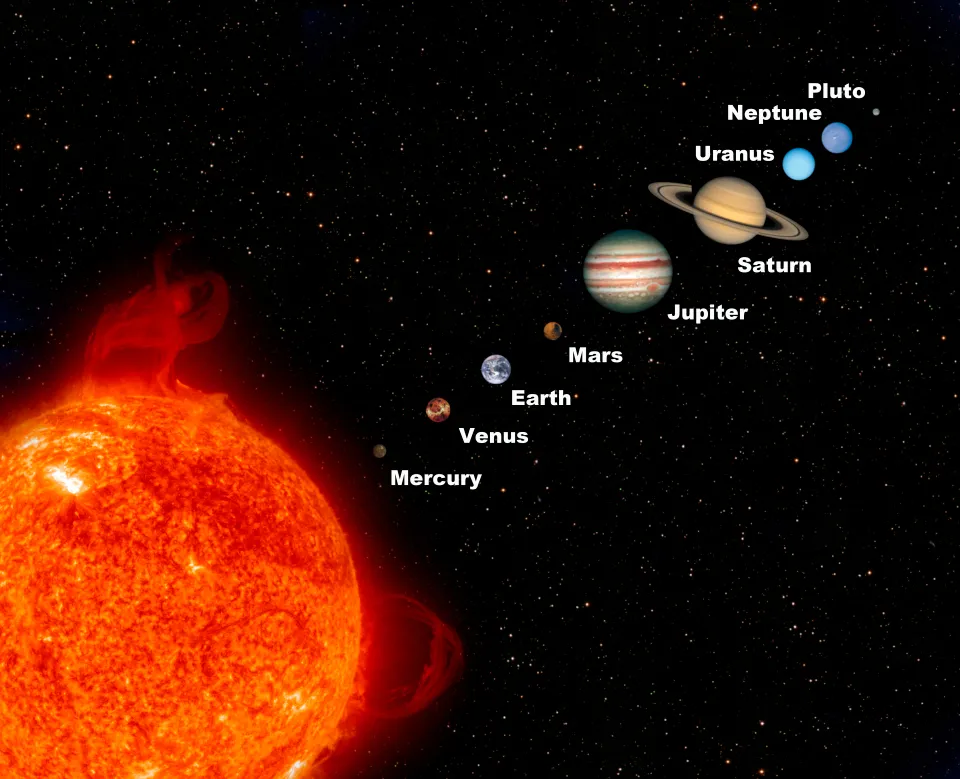

The term “planet” comes from the Greek word “planētēs”, meaning “wanderer,” reflecting how these objects move across the sky differently from fixed stars. Ancient astronomers, including the Babylonians, Greeks, and Chinese, identified five planets visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

-

Geocentric View: For centuries, planets were thought to orbit the Earth. This geocentric model dominated human understanding of the cosmos until the 16th century.

-

Copernican Revolution: Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric model, correctly placing the Sun at the center of the Solar System and showing that planets, including Earth, orbit the Sun.

-

Discovery of New Planets: Uranus (1781), Neptune (1846), and Pluto (1930) were discovered later, prompting the need for a more precise definition of a planet.

Historically, a planet was simply “a body that moves around the Sun,” but this simple description became inadequate as astronomers discovered more diverse celestial objects.

The IAU Definition of a Planet

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) attempted to standardize the definition of a planet. According to the IAU, a celestial body is a planet if it meets three criteria:

-

Orbits the Sun: The object must revolve around the Sun.

-

Sufficient Mass for a Round Shape: Gravity must pull the object into a nearly round shape.

-

Cleared Its Orbital Neighborhood: The object must dominate its orbit, removing smaller debris.

This definition famously reclassified Pluto as a “dwarf planet”, sparking public outrage and scientific debate. While the IAU intended clarity, the definition has created more confusion than resolution.

Problems With the Current Definition

There are several key issues with the IAU’s planetary definition that scientists and astronomers have pointed out:

1. Sun-Centric Limitation

The IAU definition applies only to objects orbiting the Sun, excluding exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars. With thousands of exoplanets discovered, it’s clear that a planetary definition should be universal, not limited to our Solar System.

2. Orbital Clearing is Ambiguous

The requirement that a planet “clears its orbit” is vague and difficult to quantify. Many planetary systems have debris, asteroid belts, or multiple planets sharing orbital space. For example:

-

Jupiter shares its orbit with Trojan asteroids.

-

Some exoplanets exist in multi-planet systems with overlapping orbital paths.

Does this mean such planets are less “planet-like”? The criterion is arbitrary and inconsistent.

3. Dwarf Planets and the Gray Area

The reclassification of Pluto highlighted the limitations of the IAU definition. Other dwarf planets, like Eris, Haumea, and Makemake, are similar to Pluto, yet only some meet the orbital criteria. This creates a gray area between planets and dwarf planets, leaving scientists debating which objects truly deserve planetary status.

4. Exclusion of Rogue Planets

Some planets, called rogue planets, do not orbit any star. They drift freely through space, yet by all other characteristics—they are spherical, massive, and formed like planets—they qualify as planets. The IAU definition excludes them, showing the rigidity of a Sun-centric approach.

5. Arbitrary Mass Thresholds

The IAU definition uses the concept of hydrostatic equilibrium (spherical shape) but does not specify precise mass limits. Small objects can be spherical if icy, while some larger rocky objects remain irregular. This introduces inconsistencies in classification.

Scientific Implications

These definitional problems have real scientific consequences:

-

Planetary Formation Models: Accurate classification is essential for studying planetary formation and evolution. Misclassification can skew models of Solar System development.

-

Exoplanet Studies: A definition limited to our Solar System complicates the study of planets around other stars. Exoplanet researchers often rely on mass, radius, and orbital characteristics, which may differ from IAU criteria.

-

Public Understanding: Confusion over Pluto, for example, has led to widespread misunderstanding of planetary science, affecting education and outreach.

In short, the current definition is inconsistent, arbitrary, and not universally applicable, hindering both research and communication.

Alternative Approaches to Defining a Planet

Several scientists have proposed more inclusive and flexible definitions:

1. Geophysical Definition

Some astronomers suggest defining a planet based solely on intrinsic properties, such as:

-

Sufficient mass for self-gravity to form a round shape.

-

Not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion (which would make it a star).

This approach includes dwarf planets, exoplanets, and rogue planets, focusing on the object itself rather than its orbital context.

2. Formation-Based Definition

Others propose defining planets by how they form:

-

Planets form from protoplanetary disks around stars, aggregating gas, dust, and debris.

-

Objects formed through different processes, such as brown dwarfs, would not count as planets.

This definition ties planetary identity to origins rather than current orbital dominance.

3. Inclusive, Universal Definition

A more inclusive approach would define planets by a combination of mass, shape, and formation, without limiting them to the Solar System or requiring orbital clearing. This would embrace:

-

Exoplanets

-

Dwarf planets

-

Rogue planets

-

Puffy gas giants and other extreme varieties

Such a definition reflects the diversity of planetary systems across the universe.

Why the Debate Matters

You might wonder why defining a planet is important beyond academic debates. The answer lies in both science and culture:

-

Scientific Clarity: Clear definitions help categorize celestial objects, allowing consistent research, data collection, and modeling of planetary systems.

-

Understanding Planetary Evolution: Studying all planets, including rogue and dwarf planets, improves our knowledge of planetary formation and dynamics.

-

Public Engagement: Planets are iconic in science education and culture. A consistent definition prevents confusion and sparks interest in astronomy.

-

Exoplanet Exploration: With thousands of exoplanets discovered, an adaptable definition ensures we can classify new findings accurately.

In short, how we define planets affects research, education, and our broader understanding of the cosmos.

Examples Highlighting the Definition’s Weaknesses

-

Pluto: Demoted to dwarf planet despite having a spherical shape, moons, and a complex geology.

-

Eris: Slightly larger than Pluto but also classified as a dwarf planet, showing the arbitrary nature of orbital clearing criteria.

-

Rogue Planets: Billions may exist in our galaxy, yet they are excluded by current IAU standards.

-

Puffy Gas Giants: Some planets are unusually large and low-density, challenging traditional ideas of planetary mass and radius thresholds.

These examples reveal that the current definition does not accommodate the diversity of known planets.

The Future of Planetary Definitions

As astronomy advances, the IAU definition is likely to evolve. Several directions are possible:

-

Global Consensus: Scientists may adopt a geophysical or formation-based definition that is universal and flexible.

-

Inclusion of Exoplanets: Any definition must apply to planets beyond the Solar System to remain relevant in the era of exoplanet discovery.

-

Dynamic Criteria: Planetary definitions may consider a range of characteristics, such as mass, shape, composition, and formation, rather than rigid orbital rules.

Ultimately, a modern planetary definition should reflect the diversity of celestial objects, the advances in observational astronomy, and the need for scientific clarity.

Conclusion

The controversy over what constitutes a planet highlights a fundamental issue in astronomy: our definitions are limited by historical context and our local Solar System. The IAU’s current definition, while attempting to standardize terminology, is Sun-centric, arbitrary, and inconsistent, excluding dwarf planets, rogue planets, and some exoplanets.

To truly understand the cosmos, scientists must embrace a definition based on intrinsic properties, formation processes, and universal applicability. Such a definition would not only clarify the classification of known celestial bodies like Pluto, Eris, and rogue planets but also accommodate future discoveries in the ever-expanding universe.

Planets are more than just wanderers in the sky; they are dynamic, diverse worlds that challenge our understanding and spark curiosity. By redefining what a planet is, we acknowledge the complexity of the universe and open the door to deeper exploration and discovery.

Read Also: Keep your face towards the sunshine and shadows will fall behind you

Watch Also: https://www.youtube.com/@TravelsofTheWorld24

Leave a Reply