Paleontologists have announced that a 75‑million‑year-old dinosaur — long sitting in museum collections in New Mexico under the wrong name — is actually a distinct species of duck‑billed dinosaur (hadrosaurid).

The new species has been named Ahshiselsaurus wimani, honoring the region where the fossil was originally collected.

That means this giant “duck‑billed” herbivore — part of the broader hadrosaur family — is adding a new branch to the dinosaur family tree, expanding our view of dinosaur diversity toward the end of the Cretaceous.

How Did Scientists Figure It Out — Re‑Examining Old Fossils

-

The fossil that now defines Ahshiselsaurus was originally collected in 1916. For many decades, it was classified under an already known genus — until recently.

-

In 2025, an international team re‑analysed the specimen using detailed anatomical comparisons and phylogenetic analysis (comparing bone shapes and features against other known hadrosaurids).

-

They found that the skull fragments, jaw and cranial bone structure — including elements like the jugal, quadrate, dentary, surangular, and cervical vertebrae — differ consistently and significantly from those of previously named species (for example, from the genus it had been assigned to).

-

Because the differences are in key diagnostic bones (not trivial or ambiguous parts), scientists concluded that it warrants a new genus and species rather than being a variant or immature form of an existing one.

Thus, what had been “hiding in plain sight” for over a century is now recognized properly, thanks to modern paleontological methods and re‑evaluation.

What Was Ahshiselsaurus Like — Size, Diet, and Lifestyle

-

As a hadrosaurid (“duck‑billed dinosaur”), Ahshiselsaurus would have been herbivorous, using its broad, flattened beak to efficiently shear and gather plants/vegetation.

-

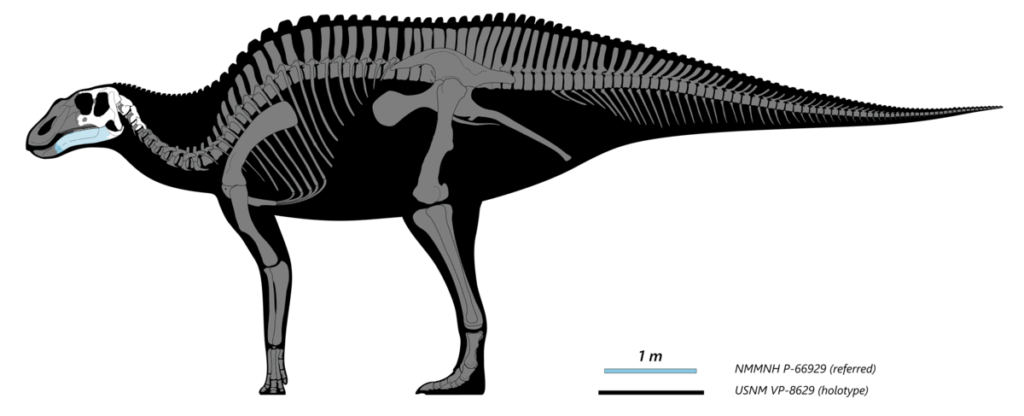

It was massive — estimates suggest it may have weighed over nine tons.

-

Its skeletal features — especially skull and jaw architecture — show adaptations consistent with heavy herbivores in the Late Cretaceous, likely thriving in rich coastal‑plain or floodplain environments.

-

Because hadrosaurids could walk on two legs or four, Ahshiselsaurus probably had similar locomotion flexibility, allowing it to forage effectively for ground vegetation or low‑lying plants.

In short: a seriously large, well‑adapted herbivore, part of a group that dominated many ecosystems in their time.

What This Discovery Means — Wider Implications for Dinosaur ScienceGreater Diversity Among Late Cretaceous Dinosaurs

The recognition of Ahshiselsaurus shows that near the end of the dinosaur era, ecosystems in what is now southwestern North America were more diverse than previously thought — there were multiple large hadrosaur species, not just a few common ones.

That in turn suggests more complex ecological interactions: different hadrosaurs might have had slightly different diets or behaviors, reducing direct competition and enabling coexistence.

Importance of Revisiting Old Collections

This discovery underscores how essential it is for paleontologists to re‑examine old fossils, especially with modern methods. Specimens collected decades (or even a century) ago may hold new secrets once re‑analyzed carefully. Ahshiselsaurus is a perfect example: it sat mis‑classified for over 100 years before scientists spotted distinctive traits.

Refining the Dinosaur Family Tree

Adding a new genus and species changes how we understand hadrosaur evolution and diversification — particularly in the Late Cretaceous of North America. Researchers will want to adjust evolutionary trees (phylogenies), reconsider how species are related, and re-examine ecological dynamics of that era.

Life, Extinction, and Ancient Ecosystems

More species means more ecological nuance: varying adaptations, potentially different habitats, resource use, and survival strategies. Studying Ahshiselsaurus (and similar finds) helps build a richer, more accurate picture of dinosaur-era ecosystems — what plants they fed on, how populations were structured, and how extinction (at the end of Cretaceous) impacted varied dinosaur lineages.

What We Still Don’t Know — And What’s Next

What We Still Don’t Know — And What’s Next

-

The holotype fossil is incomplete. While skull fragments and cervical vertebrae allowed identification, we lack a full skeleton (limbs, tail, etc.). More fossils would help reconstruct the full body shape, gait, and posture.

-

Details about its precise environment, diet preferences, life history (e.g. growth rate), social behaviour remain unknown — these require additional finds and contextual analysis (geology, plant fossils, isotopic studies).

-

Because the specimen lay mis‑classified for decades, there is a chance other overlooked specimens exist — re‑surveying museum collections may reveal more individuals, or even close relatives. As scientists involved noted: this discovery is not the “final lap,” but the beginning of a broader re‑exploration.

Final Thoughts

The identification of Ahshiselsaurus wimani is an exciting reminder: even in a field as old as paleontology, science is never “done.” What we thought was settled may turn out to conceal new surprises — species, stories, and biodiversity we missed.

A duck‑billed giant, hidden in plain sight for over a century, now emerges as a brand‑new dinosaur species — reshaping our understanding of dinosaur diversity, ecosystems, and evolution near the end of the Mesozoic.

If you like — I can also prepare a short summary (~300–400 words) of this discovery — good for social‑media posts or quick reference.

Read Also: The Race to 300 mph: Will Hennessey or Koenigsegg Break the Speed Record in 2025?

Watch Also: https://www.youtube.com/@TravelsofTheWorld24

Leave a Reply